Legal Perspectives on Oral Appliance Therapy and Dental Sleep Medicine

Dr. Ken Berley is an author, attorney and dentist with a practice focused on the treatment of sleep-disordered breathing and TMD. He is a diplomate of the American Board of Dental Sleep Medicine, a lecturer, and a consultant in the areas of risk management and the development of a successful dental sleep medicine (DSM) practice. In this interview, Dr. Berley provides a unique perspective on oral appliance therapy and describes how this treatment option can dramatically improve the lives of patients.

DR. NEIL PARK: Can you share a little bit about your background as both a dentist and attorney?

DR. KEN BERLEY: I graduated from dental school and started my practice in 1980, but I had always been interested in the law. In 1991, I started law school at night and practiced dentistry in my two dental offices during the day. It was a long four years, but I finally graduated from law school in 1995.

NP: But then you went back to dentistry, right?

KB: Well, I never left dentistry. For 10 years, I was the managing partner of a law firm in Little Rock, Arkansas, and managed my dental offices. I learned a lot about sleep deprivation during those years. So for 23 years now, I’ve been an attorney, and for over 35 years, I’ve been a practicing dentist.

NP: OK, so let’s first start with the scope of your legal practice.

KB: My concentration is in the field of dental sleep medicine. I primarily represent dentists who have state board complaints or are undergoing insurance audits. Additionally, I consult with defendants’ attorneys and help fashion defense strategies in malpractice cases and provide expert testimony.

NP: So you’re involved in the very noble enterprise of getting dentists out of trouble.

KB: Yes, I’m on the good side.

NP: We love to hear that. And what’s the nature of your dental practice?

KB: We’re probably 90% dental sleep medicine and 10% general dentistry.

NP: You and I met last year at an ADA meeting that was about sleep disorders. I was the neophyte trying to learn my way around, and you were one of the leaders of the group there. You’re very well-established within this field of dental sleep medicine. Can you tell us how you got involved?

KB: It started with me realizing that both my grandfather and my father died of a stroke in the middle of the night — and they physically looked just like me. I started becoming very, very aware of dental sleep medicine and fabricated an appliance for myself many years ago. Additionally, at that time, I was actively treating a lot of TMD patients who also had sleep-disordered breathing. So we were finishing up those TMD cases and using an appliance that actually protruded the mandible at night, and for many of those patients, not only were their TMD issues improved, but they also kept self-reporting that they were sleeping much better. Slowly but surely, you start evolving and figuring out that there are things we don’t know. It became obvious that most adults slept better with the mandible supported in a slightly protruded position. Then we had a patient come in who had been recently married and, in preparation for his new life, he had a sleep study performed because he knew he snored a lot. And of course, his physician put him on a CPAP, but he could not tolerate it.

NP: Is that a common thing — that people can’t tolerate CPAP devices?

KB: Oh, yes. In fact, there’s a significant volume of research demonstrating the percentage of patients who can actually tolerate CPAP treatment, and the numbers are really poor. About 25% of patients, maybe after a year, are actually using a CPAP. And by “using it,” I mean they are utilizing the CPAP about four hours per night. So even “utilization” as it’s defined isn’t real utilization. A very, very small percentage of patients actually use a CPAP all night, every night. That’s where dentists come in. We have a solution for that. We can work with our medical colleagues and provide life-saving therapy for patients with obstructive sleep apnea and snoring. Anyway, this patient came in for a consultation — and he and his spouse were in counseling after only six months of marriage. He had already been relegated to the second bedroom, and he said, “Ken, I’ve been on the internet and I understand there are things that you can do to help.” And, Neil, I knew nothing about dental sleep medicine.

About 25% of patients, maybe after a year, are actually using a CPAP. And by “using it,” I mean they are utilizing the CPAP about four hours per night.

NP: I can certainly relate to that.

KB: I knew how to take two impressions, so I said, “I think I can help you.” And he turned out to be my first DSM patient. And I did everything wrong — I didn’t follow protocol, and I didn’t have a prescription. I had nothing except a desire to help this patient save his marriage. That was many years ago now, and he has twin boys who are currently teenagers. His wife now brings the appliance in when she hears him snoring again. She essentially decides when the appliance needs to be titrated.

NP: He’s your patient, but his wife is your fan.

As a dentist, attorney and coauthor of “The Clinician’s Handbook for Dental Sleep Medicine,” Dr. Ken Berley is shaping the way dentists treat patients who suffer from sleep-disordered breathing.

KB: Yeah, she’s my friend. She says, “Ken, you know, he’s snoring again.” Sleep-disordered breathing or obstructive sleep apnea is a progressive condition. And these patients do need to be followed, and there will be continued titrations and adjustments. But he became my biggest fan. He told the sleep physician who was treating him, and I started getting referrals. And then all of a sudden, I realized that I was treating a serious, life-threatening condition and I knew nothing about it. I became committed to learning everything I could about sleep medicine and the treatment of sleep disorders utilizing mandibular advancement. Now, things have progressed to the point where we’re actually able to help develop protocols and help guide the direction of the profession. So it’s been quite the journey.

NP: You’ve definitely made quite a journey. Actually, I have your textbook published by Quintessence. Congratulations! It’s a fantastic book.

KB: Thank you.

NP: You know, there are two kinds of textbooks in dentistry. There’s the one that’s so esoteric and highly detailed that you just use it for reference, and then there’s the textbook that’s very, very readable, that you can read from cover to cover — which I did, by the way — and really get an understanding of the topic. And that’s what you and your coauthor, Dr. Steve Carstensen, have achieved.

KB: Thank you. It wasn’t my intention. When we were initially approached by Quintessence, I wanted a textbook, something that could go to a dental school. But Quintessence, in their wisdom, wanted a book that dentists right out of school, knowing nothing about DSM, could actually pick up and understand to a point where they could go on to treat a patient successfully. So all the way through the editing process I was attempting to make the book more readable. That was the goal, and I hope we’ve accomplished that.

NP: You certainly have, and I highly recommend that everybody get this book and read it. Ken, how many people in this country suffer from sleep problems?

KB: If you look at the scenario ranging from snoring all the way to full obstructive sleep apnea, we know that at least 60% of the population snores regularly. Therefore, approximately 200 million people in this country suffer from some level of sleep-disordered breathing. The NIH says that 60% of all senior citizens have obstructive sleep apnea. Their definition of senior citizens, I hate to say, is someone over 40 years of age.

NP: The people on the far side of the spectrum, the people with OSA, the people with hypopneas — what are those numbers?

KB: I’ve heard that up to 52 million Americans have clinically significant sleep-disordered breathing, meaning that these are the people for whom the disease is going to result in a shortened life expectancy.

NP: Let’s talk about the fairly standard protocol that a dentist would use in screening those patients and treating them. My understanding is that most state laws say that only a physician can make a definitive diagnosis of sleep apnea, so what dentists typically do is screen patients, ask them if they’re snoring, ask them if they’re drowsy during the day and other questions like that, and then refer them to a physician to do the required tests and make a definitive diagnosis. Did I capture the standard protocol correctly?

KB: Close. The first thing we need to address is the comment you made about state law. We have five states that have made some type of statement by the board that says dentists should not be diagnosing; they should not be providing treatment without the involvement of a sleep physician. But very few states have actually come out with a position yet, though that’s about to change. In October 2017, the ADA came out with their policy statement on the role of dentists in the treatment of sleep-disordered breathing. And as you probably know, once the ADA speaks, everyone else kind of lines up. There are five different states right now in the process of adopting that ADA policy statement or a version of it.

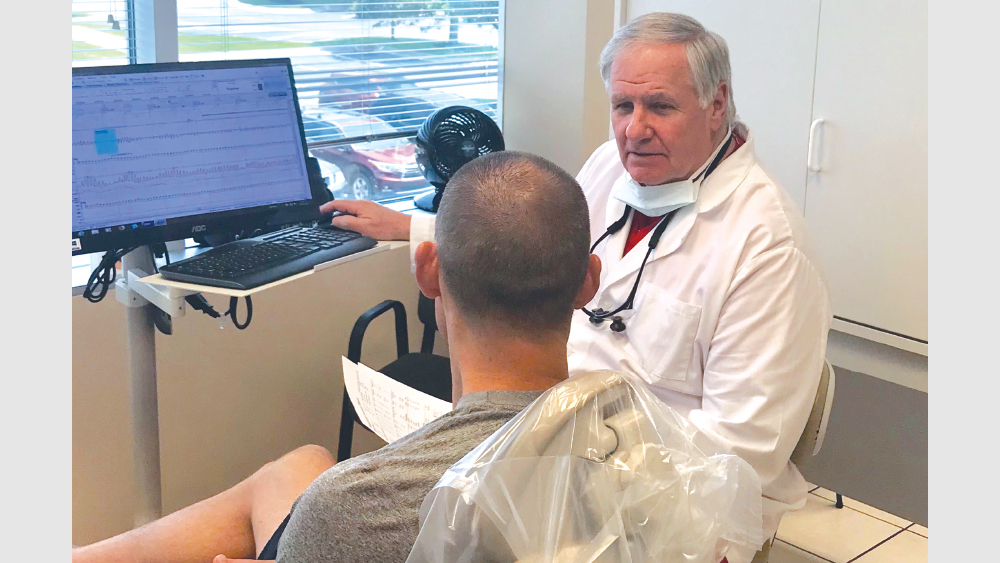

When a patient is screened and shows significant signs of sleep-disordered breathing, Dr. Berley suggests treating the patient provisionally with the Silent Nite® Sleep Appliance, a protocol that minimizes symptoms during the interim between screening and a definitive diagnosis made by a sleep physician.

NP: The policy statement is a double-edged sword, right? It says that it is within the scope of the dental practice to do this screening for sleep apnea. But by the same token, then it says that —

KB: That they’re supposed to be referred.

NP: Right.

KB: That is unique for dentistry because we haven’t historically screened for things that we then can’t touch. But if you look at the definition of the practice of dentistry, obviously screening and treating OSA is well within our definition. We have approximately 4,000 sleep physicians in this country.

NP: But, Ken, 4,000 sleep physicians, more than 50 million people with a life-threatening condition —

KB: The numbers don’t work — that’s the big quandary that we have. We have approximately 195,000 dentists. And once the ADA says you need to screen, if you don’t screen there could be legal ramifications resulting from that. Over the next few years, all dentists will begin screening their patients and sending them to the local sleep physician. Obviously, there are way too many patients who are about to be screened and not enough sleep physicians to adequately diagnose and manage treatment. The numbers are out of control.

There are way too many patients who are about to be screened and not enough sleep physicians to adequately diagnose and manage treatment. The numbers are out of control.

NP: So 195,000 dentists are almost mandatorily going to screen for this disease, and they’re trying to refer them to 4,000 sleep physicians. What’s the typical amount of time from the appointment in which a dentist screens the patient and makes that referral to when the patient actually receives some treatment?

KB: In our area, it can certainly be months, and many times it’s four months or more.

NP: So when your patient is in the chair, you say: “Hey, you might have this life-threatening, horrible disease. Let’s get things going, so in six months we can get you treated.”

KB: Exactly. And one of the things that I’ve proposed is that, once we screen patients and know they have significant symptoms of OSA, I think it would be foolish of us not to provide some type of provisional therapy for those patients. In fact, I had a 25-year-old patient who I knew had significant daytime sleepiness. And in her case, it was four months before she saw the sleep physician. She fell asleep while driving on the interstate and hit a bridge abutment, and luckily she survived. But it was a miracle that she lived. By the time we finally got her tested, she had what we call an apnea-hypopnea index — that’s counting the total number of apneas and hypopneas, and then dividing it by your sleep time — of 47 events an hour. So almost one event per minute, she stopped breathing. The 25-year-old woman was put on a CPAP. I don’t care where you are — that’s not going to work. And now her condition is absolutely controlled by oral appliance therapy. If I had put her on a provisional appliance of some type — something that wasn’t terribly expensive and I could provide to her quickly — and instructed her to use that until the time she was able to go to a sleep physician and get a definitive diagnosis, that accident may have been prevented. Additionally, I’ve had a number of patients who have had strokes or heart attacks while waiting on treatment.

NP: So just to restate your point: You’re proposing a protocol change where you do some kind of a provisional treatment before the patient even meets with the sleep physician for a definitive diagnosis.

KB: Yes.

Helping dentists to successfully provide oral appliance therapy to their patients, Dr. Berley has written the legal document “Informed Consent for the Silent Nite Sleep Appliance — Provisional Mandibular Advancement Device.” It’s available for free at glidewelldental.com/informed-consent.

NP: And you have a protocol that will work for dentists throughout the U.S.?

KB: Dentists and physicians work on provisional diagnoses. We go in, we examine a patient, and we make a determination of what we’re going to have to do provisionally. Many times we have to do tests, X-rays, or other things to determine a final diagnosis and a final treatment plan. Physicians are the same way. If you show up in an emergency room with chest pains, they’re not going to wait for the lab results to confirm it; you’re going to get immediate treatment based on a provisional diagnosis that you’re having a heart attack of some type. All I’m saying is that we need to be doing the same thing in dental sleep medicine. If we have an appliance, which Glidewell does, that can be done quickly without a lot of the expense, and we can get it in the patient’s mouth and they can wear that provisionally until we get a definitive diagnosis — that is the better treatment. The Silent Nite Sleep Appliance is custom-fabricated for that patient. It’s based on either scans or impressions — however the dentist wants to do it. That appliance can be done quickly. Since there is not a diagnosis yet, there’s no insurance to file, so it would be a cash type of arrangement with the patient.

But the beauty is that these appliances are going to last longer than the three or four months it takes to get the patient into the office. So if the patient is put on CPAP, the appliance could actually be worn with the CPAP. It moves the bottom jaw out and helps open the airway so the CPAP pressure could be much less. And if the sleep physician determines that CPAP is the best therapy, then combination therapy — CPAP plus Silent Nite — results in a much more tolerable amount of pressure being used in the CPAP. So I think it’s absolutely the best of both worlds. Once the Silent Nite is no longer functional, another appliance could be made. Or once there’s a definitive diagnosis, if the patient wants, say, a more sturdy appliance, for lack of better terms, that could be done also.

The Silent Nite Sleep Appliance is custom-fabricated for that patient. It’s based on either scans or impressions — however the dentist wants to do it.

NP: Dentists have been put in a somewhat uncomfortable situation where we’re asked to screen for sleep-disordered breathing, and then we have to ask the patient to leave without any kind of treatment. So walk me through this protocol for the dentist who wants to place a provisional device.

KB: My suggestion for dentists who are going to do this is that they need to develop a strong relationship with a physician they’re going to refer these patients to. The sleep physician needs to understand that we are doing this provisionally. We’re doing it to minimize symptoms in the interim between screening and definitive treatment, whatever that is. When the patients show up with a Silent Nite Sleep Appliance, the physician already understands they’ve been screened, they’ve been found to have significant symptoms, and out of an abundance of caution, the appliance has been provided to serve the patient until the sleep physician determines a definitive treatment. That sleep physician needs to know that we’re not taking away his right or authority to be the quarterback of our team. We’re just providing something provisionally until that diagnosis is made.

You need to reach out to that sleep physician and let him know: No. 1, you’re screening; and No. 2, you need a place to refer these patients. So let the sleep physician know he’s about to benefit directly from your introducing the screening protocol. However, for patients with significant symptoms, you want him to understand that you’re initiating this protocol to provide a provisional appliance during that interim. So once that is established, it becomes quite simple. You screen, then you determine whether or not the symptoms are significant enough to provide a provisional appliance. That’s almost going to have to be a judgment call as to whether or not the patient’s life is impaired due to sleep-disordered breathing (SDB). Are they falling asleep at inappropriate times? Then you have the whole snoring issue. Are the SDB symptoms impairing the quality of life of the patient’s family?

Once you screen, you make the clinical decision of whether or not the patient’s SDB symptoms are significant enough to recommend the fabrication of a Silent Nite appliance. So you provide that appliance and then a referral form to the sleep physician.

NP: Well, Ken, I think you’ve made a great case for this provisional therapy.

KB: Thank you.

NP: We’re fortunate that we have you, an expert in dental sleep medicine as well as a practicing attorney. I understand that you have produced an informed consent form to help dentists stay out of trouble during this process.

KB: That’s right. But it’s important to remember that one of the elements of consent is that patients need to have time to not only read and understand the document and have the document explained to them, but also ask questions.

NP: Good point. Ken, in the informed consent form, there’s a specific provision about tooth movement. Is there any way to prevent that or mitigate any tooth movement when the patient wears the Silent Nite device?

Along with his two assistants, Dr. Berley provides patients with an interim solution to minimize their symptoms while they wait for a definitive treatment.

KB: The issues that we’ve had up to this point dealing with sleep appliances have all centered around tooth movement, and in that consent form, it specifically mentions what we call a morning repositioner. The Silent Nite functions by moving the lower jaw out, and as a result, the retrodiscal tissues fill up with fluid. So when the appliance is removed in the morning and patients go to bite, their back teeth don’t hit. What we’re doing in conjunction with Glidewell is providing a wafer with these appliances called an AM Aligner. It’s a thermoplastic type of wafer that can be heated up in warm water, and the patient bites into that aligner. You’re capturing the centric bite on that patient as it is the day that you deliver this appliance. We instruct patients to take their Silent Nite out in the morning, clean it and stow it away. Not only do patients need to brush their teeth and place the AM Aligner in their mouth, but we also tell our patients to get in the shower to get the muscles nice and warm, and gently bite into that AM Aligner. As patients bite into the AM Aligner, they can actually feel their back teeth coming together. We call it recapturing their bite. Once those back teeth are hitting and the bite feels normal, they’re finished with the morning repositioner. This certainly minimizes risk of tooth movement.

NP: Well, that’s great advice. And that comes with the appliance when they order it from Glidewell?

KB: Yes.

NP: With the kind cooperation of our guest, we’re able to offer Chairside® magazine readers two things: First, if you go to glidewelldental.com/informed-consent, you’ll be able to download the informed consent form that dentist-attorney Dr. Ken Berley has written. This is what your patient needs to understand to go forward with this provisional treatment. And you’ll also receive a 25% discount on the new textbook from Quintessence, “The Clinician’s Handbook for Dental Sleep Medicine,” by Drs. Ken Berley and Steve Carstensen. It’s a great read. You’ll read this from cover to cover and really gain a tremendous understanding of the field.

Ken, thanks so much. It was a pleasure to be with you today.

KB: Thank you, sir.

AM Aligner is a product of Airway Management Inc.